Clinical Pearls for the Flat Foot – Part 1

When adults present to your clinic with ‘flat feet’, it can present an interesting enigma – why do some flat feet function normally and pain-free, yet other are painful and cause disability? We now know the answer to that question is the soft tissue changes that occur in some patients and not in other.

The dynamic supporting structures of the foot include:

- Plantar aponeurosis

- Posterior tibial tendon

- Plantar intrinsic musculature – Dr Luke Kelly and colleagues have done some wonderful work in this area.

Whilst many are taught that the posterior tibial muscle and tendon are responsible for ‘holding up the arch’, we know through cadaveric studies that the plantar aponeurosis has a 3-fold greater power of arch support compared to the posterior tibial tendon.

The static supportive structures of the foot include:

- Spring ligament complex

- Superficial deltoid ligament

- Interosseous talocalaneal ligament

- Long and short plantar ligaments

- Plantar aponeurosis – note both a static and dynamic supporting structure.

Two of the most prominent researchers in this area, Dr Jonathan Deland and Dr Mark Myerson, have repeatedly demonstrated that the sequential failure of these key ligaments is what causes a pathological flat foot, rather than an isolated failure of the posterior tibial tendon. This is why we prefer the term ‘adult acquired flatfoot’ rather than ‘posterior tibial tendon dysfunction’ to describe the much broader pathology.

That being said, it is important to note that patients will have a pre-existing flat foot and pathology will start in the posterior tibial tendon. The tendon will become inflamed and painful which is the first stage in any classification scheme. Accurately diagnosing patients with posterior tibial tendinopathy or tenosynovitis and managing them appropriately can have a drastic effect and stop them from progressing into a much more disabling pathology.

A thorough history taking is vital in these patients. They will usually give some good clues in their history. These may include:

- A history of always having flat feet

- More recently one foot has become painful

- They are aware of swelling around the posterior aspect of the medial malleolus

- In some patients they’ll be aware that one foot has become even flatter

- Some patients may report some improvement in pain when wearing hiking boots

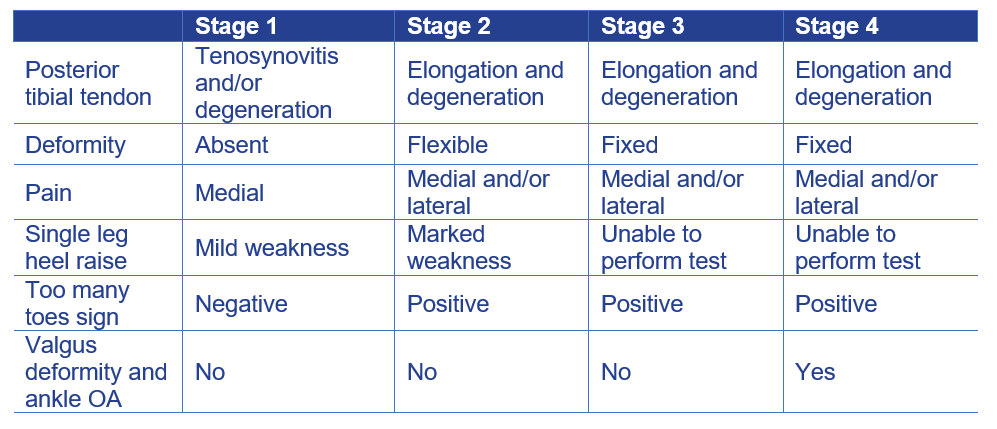

The key with the clinical examination is to conduct assessments which enables you to classify the patient. We recommend the following classification scheme based on the 2007 Myerson classification scheme and the 1989 Johnson & Strom classification:

The clinical examination should include the following:

- Gait assessment – look for a limp which indicates pain and impairment. You may also detect the foot stays pronated in late midstance, when in fact it should be resupinating.

- Single leg heel raise – arguably the most critical examination in these patients as this gives a good indication if there is ligamentous failure or not.

- Jack’s test – look for resupination of the arch and external rotation of the leg.

- Single leg Rhomberg – a simple balance test can be revealing for both the podiatrist and the patient.

- Joint ROM (hip to toe) – is the deformity rigid or flexible?

- Manual muscle testing – by isolating the posterior tibial muscle, both you and the patient can feel the weakness.

- Supination lag – another muscle test where the patient is able to see the affected foot isn’t able to come towards the midline effectively.

- Palpation for pain – is the pain isolated to the medial ankle or is the lateral aspect of the subtalar and ankle joints involved?

A thorough history and physical examination, coupled with a good understanding of the pathophysiology is vital in understanding the best treatment options for patients. If both you and the patient has an understanding of the extent of the pathology (i.e. isolated to the posterior tibial tendon or more widespread ligamentous involvement), effective treatment can be initiated.